Introduction: Is Pacing in Dogs Really More Efficient?

There is a widely held belief in the dog world that a pacing gait—where a dog moves both legs on the same side of the body together—is more energy-efficient than a trot. That pacing is a restful gait, which allows for energy conservation. However, biomechanical studies on both quadruped animals and quadruped robots suggest otherwise. In fact, pacing at trotting speeds is often compensatory, meaning the dog is likely adjusting its movement from a contralateral gait (trot) to an ipsilateral gait (pace) to avoid the torque inherent in a contralateral gait. Understanding why this happens, and what we should be doing about it, is crucial for dog owners, trainers, and breeders.

Trot vs. Pace: What’s the Difference?

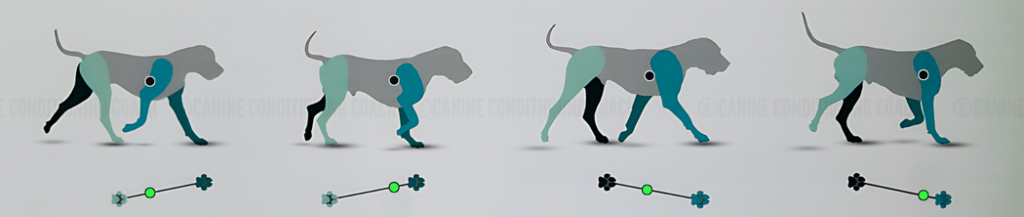

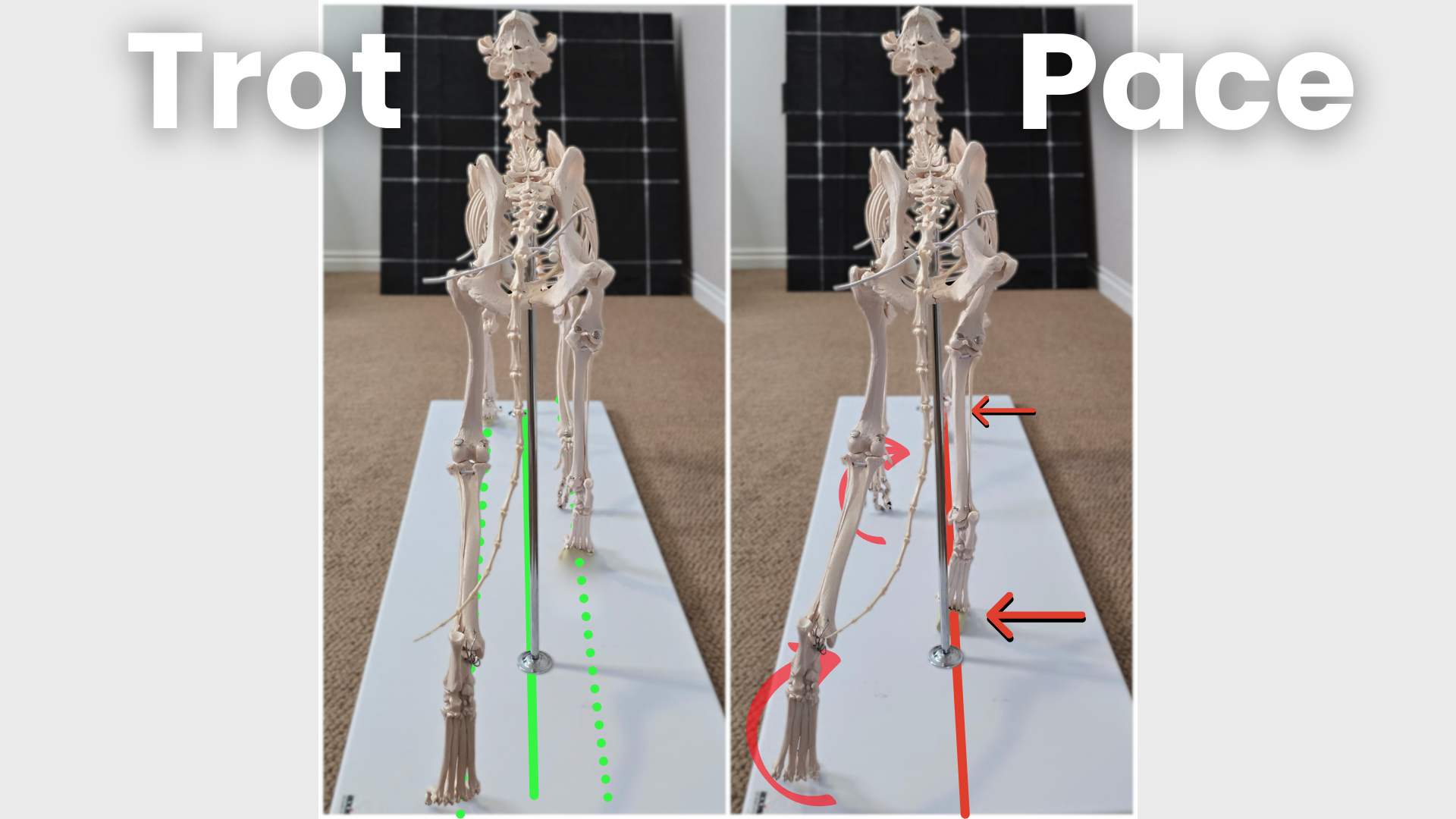

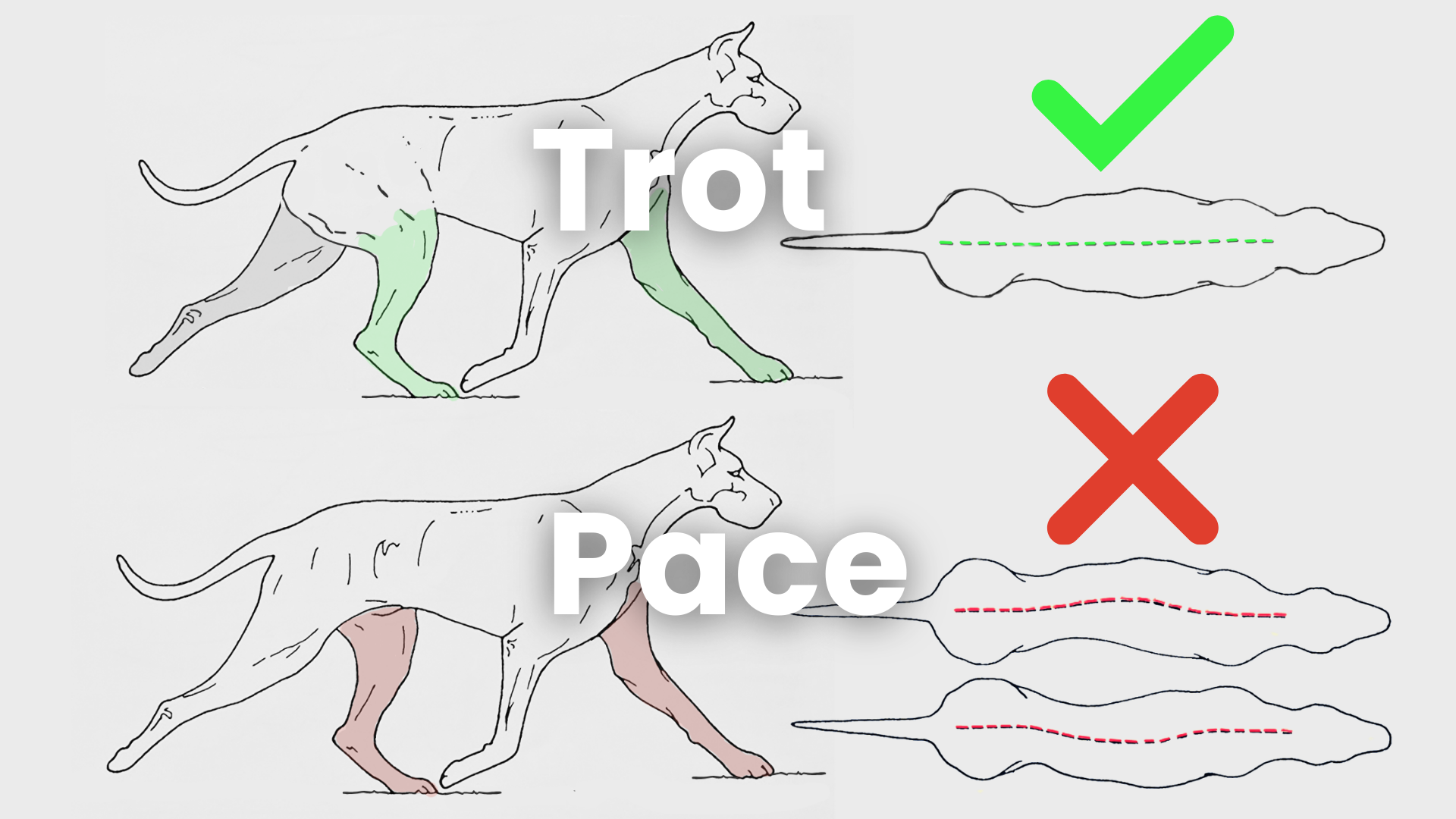

Trot (Contralateral Gait): Contralateral means opposite (contra) side (lateral). During the trot, the dog moves contralateral limbs together, in a 2-beat pattern, where 2 diagonal limbs are touching the ground simultaneously, while the other 2 diagonal limbs are lifted.

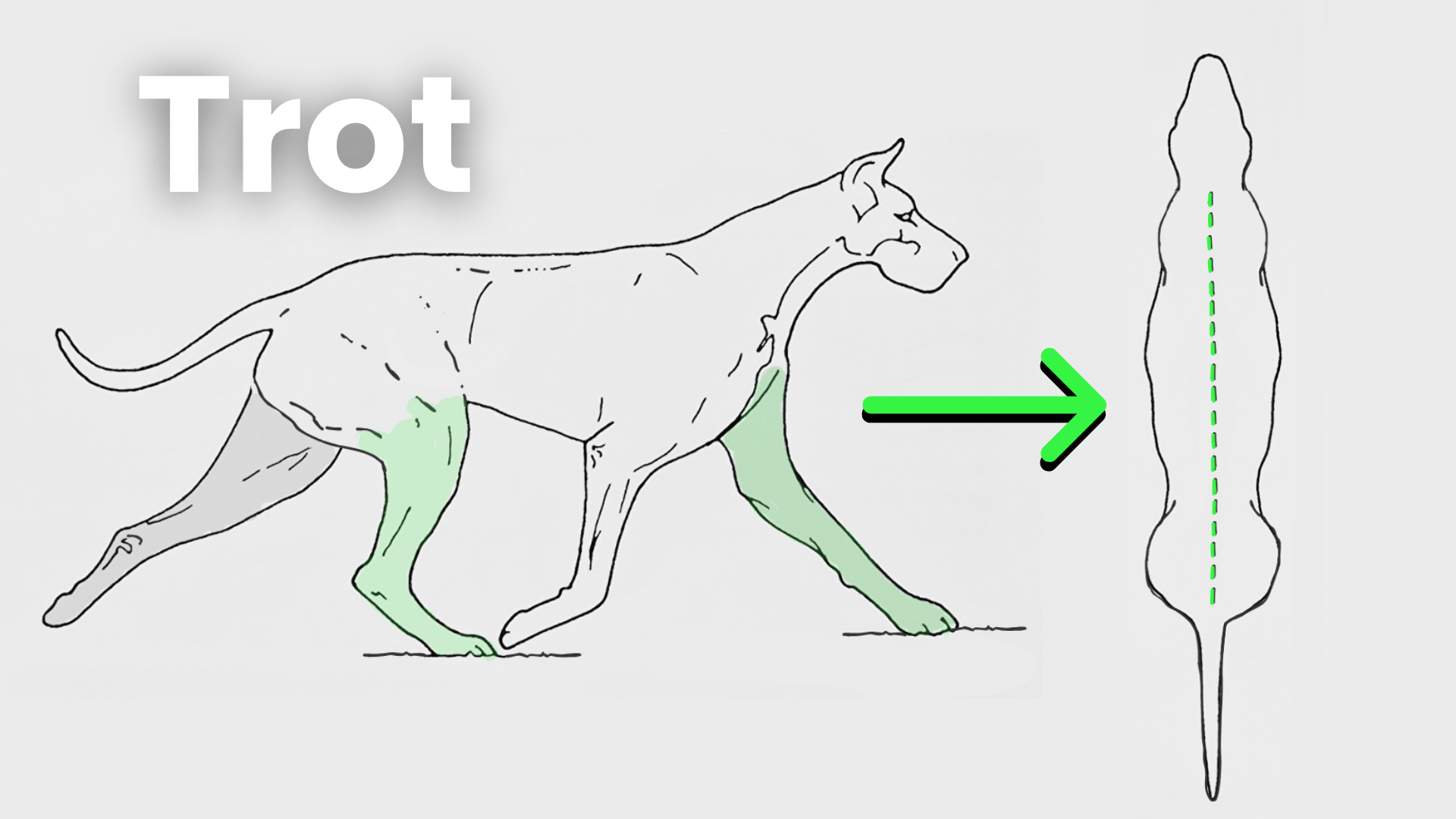

Moving diagonal limbs together means limbs from opposite sides of the body can support the weight of the torso, allowing for the Center of Gravity (CoG) to easily remain balanced between the moving limbs.

In the photo above you can see the CoG during the trot highlighted in the green circle above. See how it falls on the line of the footfalls? This means the CoG is balanced.

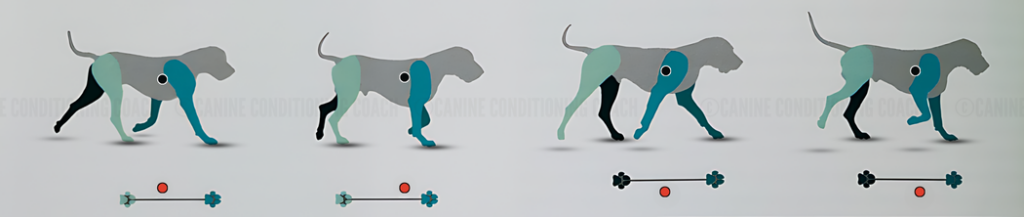

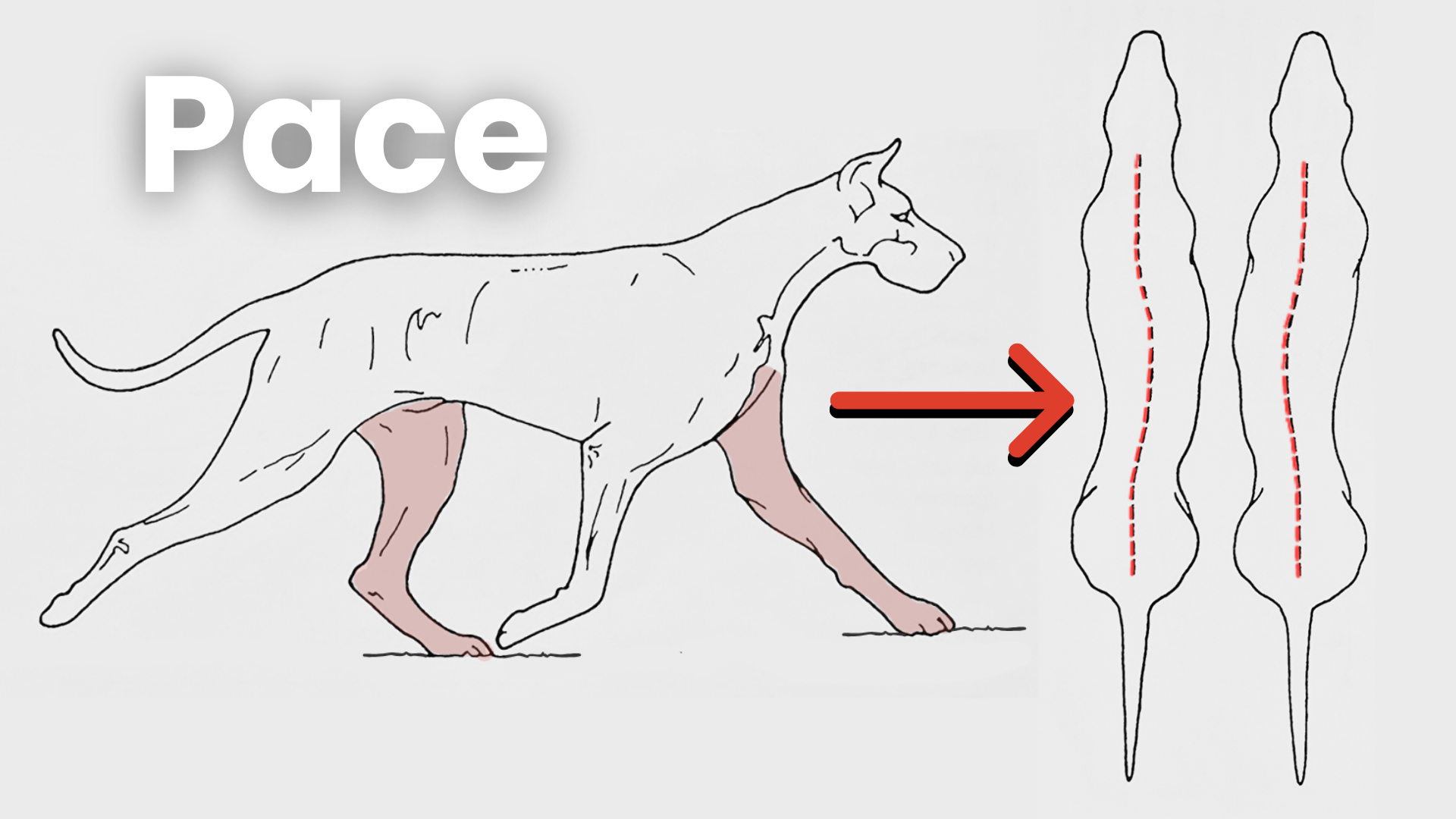

Pace (Ipsilateral Gait): Ipsilateral means same (ipsi) side (lateral). During the pace the dog moves the same-side legs together in a 2 beat pattern, where both right legs are touching the ground simultaneously, while the left legs are lifted, and vice versa.

Moving ipsilateral limbs together means the Center of Gravity (CoG) does not naturally align above the limbs. In order to balance, the dog has to shift the CoG laterally to compensate. This creates a side-to-side swaying motion, which requires additional energy to stabilize.

In the photo above, you can see the CoG during the pace highlighted in the red circle. See how the CoG falls off the line of the footfalls? This means the CoG is unbalanced, and requires a lateral displacement of the torso to compensate.

View from Above: Trot vs. Pace and Center of Gravity

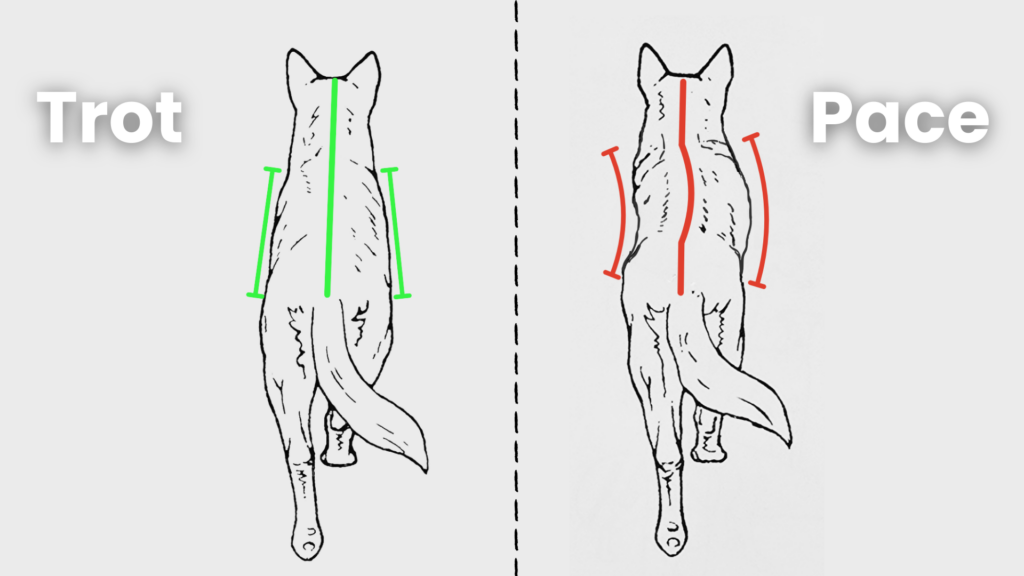

When viewed from above, the differences between the trot and pace become even more apparent.

Trot: In a contralateral gait, the opposing limbs naturally adduct slightly under the center of gravity. Because the loaded limbs are on opposite sides of the body the dog is able to balance with minimal lateral displacement of the torso. This allows the CoG to remain relatively stable throughout the gait cycle, reducing unnecessary energy loss.

Pace: An ipsilateral gait does not balance the CoG in the same way. In order to maintain balance, the dog must shift the torso to the side, displacing the torso laterally to align above the ipsilateral limbs. As the dog changes from the right limbs to the left limbs, the CoG must then shift to the opposite side.

This results in a pronounced side-to-side movement or “wiggle” commonly associated with pacing. Lateral displacement of the CoG with each stride requires additional muscular effort to stabilize, leading to a higher energy cost compared to the naturally balanced trot.

The Trot is just More Efficient

Studies on both animals and quadruped robots have demonstrated that trotting is the most energy-efficient gait at moderate speeds.

This is because:

- Balanced CoG Movement: The diagonal limb movement naturally stabilizes the body, reducing the need for excess muscular effort.

- Reduced Lateral Oscillations: In a trot, most energy is directed forward rather than being wasted on unnecessary side-to-side sway.

- Lower Energy Expenditure: Trotting minimizes the ground reaction forces (GRFs) needed to maintain balance, making it a more sustainable and efficient gait

The Hidden Cost of Pacing: More Lateral Movement = More Energy Waste

In contrast, the pacing gait requires the dog to make several biomechanical adjustments that increase energy expenditure:

- Lateral Sway: Because both legs on one side move together, the dog must shift its CoG further from side to side, creating a rolling motion with each stride.

- Compensatory Limb Movements: The grounded limbs must adduct (move under the body) while the free limbs must circumduct (move in a wider arc) to avoid interfering with the grounded limbs. This further increases energy loss.

- Increased Muscular Effort: Stabilizer muscles in the core and medial/lateral hip and shoulder stabilizers must work harder to prevent excessive swaying, which increases overall energy cost.

Quantifying the Energy Cost of Pacing

Biomechanical studies and quadruped robot research suggest that excessive lateral motion can significantly increase energy expenditure. A key formula used in gait analysis is:

E_{total} = E_{forward} + E_{lateral} + E_{vertical}

Where:

E_{total} is the total energy cost of movement.

E_{forward} is the energy used for forward propulsion.

E_{lateral} is the energy lost due to side-to-side motion.

E_{vertical} is the energy used for vertical stabilization.

In an efficient gait like a trot, E_{lateral} is minimized, allowing most energy to be directed into forward movement. In contrast, pacing increases E_{lateral}, which can result in an estimated 10-30% increase in total energy expenditure based on biomechanical modeling and quadruped locomotion studies.

When IS Pacing More Efficient?

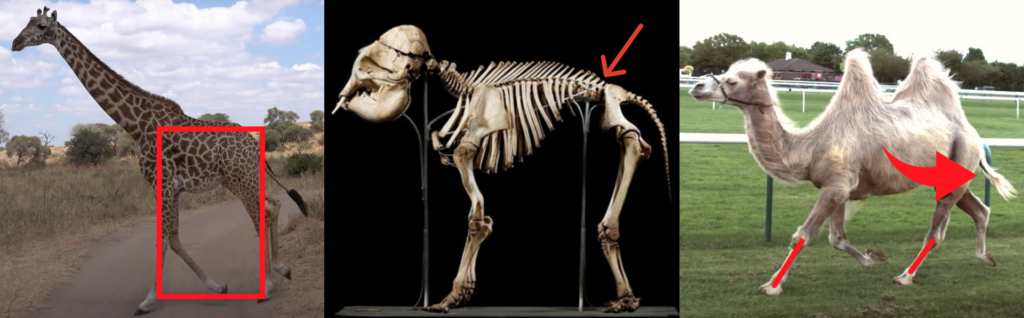

While pacing is typically compensatory in dogs, certain species with may find it more efficient due to unique body structure and biomechanical adaptations.

Giraffes naturally prefer an ipsilateral gait due to their tall, elongated limb structure where limb length exceeds the length of the torso. In animals taller than they are long, trotting would result in the limbs colliding beneath the body, and the need for additional compensation like sidewinding or crabbing. This can also be seen in other species where limb length exceeds torso length like hyenas and maned wolf.

Elephants generally move in a pacing-like lateral sequence rather than a trot. Due to their massive size, and the resulting stability requirements, elephants have evolved a skeleton with only 3 lumbar vertebrae (compared to 7 in dogs). As such they lack the ability to rotate the lumbar spine in the way trotting requires.

Camels predominantly pace rather than trot because their thoracic spines are surprisingly flexible on the dorsal plane allowing for the CoG to be displaced through rhythmic lateral spine flexion and little to no extra effort. Pacing also minimizes vertical oscillations, which is particularly beneficial in soft desert terrain where sinking into the sand would increase energy cost… So this unusual spine flexibility is likely an evolutionary adaptation.

Why Would a dog Choose to Pace?

Since a pacing gait is naturally used as a transitionary gait for speeds faster than a walk but slower than a trot, some medium/large dogs will use this gait when on leash and are being “forced” to gait at a human walking speed. However, given a longer leash (long line or flexi) or more speed, a normal, healthy dog should easily transition out of a pace into a trot. Dogs who can’t or won’t transition out of a pace into a trot OR who fall back into a pace are likely avoiding the torque inherent in a contralateral gait and compensating for discomfort or pain by substituting a pace. Some key reasons include…

Neurological Conditions

Dogs with stenosis, transitional lumbar vertebrae (LTV), disc bulge/herniation, and tethered cord syndrome / cauda equina syndrome may find the torque (rotational forces) of a trot produces neurogenic pain, making trotting uncomfortable, leading them to opt for a pace instead.

Soft Tissue Strain

Issues like iliopsoas or gracilis strain can result in compensatory pacing as a means of offloading muscular effort to areas that are less painful. This type of compensation can make pacing a better choice as a different muscle recruitment pattern can be implemented, and the painful areas can be avoided.

Musculoskeletal Pain

Hip dysplasia, arthritic changes to the stifle, and other chronic inflammatory issues of the pelvic limb can make flexing the hip and stifle painful. This can bias a dog toward circumducting the affected limb or limbs. Circumduction (where the limb sweeps out to the side following a circular path rather than tracking straight forward beneath the torso) is more easily executed in a pacing gait than in a trot.

Spinal Degeneration

Certain spinal conditions like spondylosis where the vertebral bodies develop an overgrowth of bone / bony spurring, and the adjacent vertebrae begin to fuse will need to pace. Similarly to elephants, these dogs simply no longer have the rotational mobility through the lumbar spine needed in order to trot properly.

What Should You Do If Your Dog Paces?

If your dog consistently paces instead of trotting at moderate speeds, it’s worth investigating further.

Observe the Context

Is your dog pacing only when on leash? How does their gait respond when you increase and decrease speed? What is their default gait when moving at moderate speed, freely in the yard? If you’re not sure, record video and watch in slow motion.

Check for Discomfort

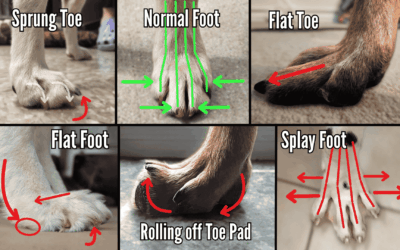

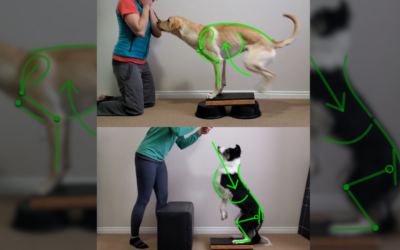

Look for other signs of pain, such as stiffness on rising, postural changes that include roaching (lumbar flexion), reluctance to jump into the car or ascend stairs, behavioral changes / increased sensitivity to stimuli or difficulty executing certain conditioning exercises like Backing Up, Fold Back Down, Plank, Rear Foot to Hand Target, or Front Foot Side Stepping.

Record Video

Record Gait Analysis Video of your dog shot from the side, front, and rear, at walking speed, trotting speed, and cantering speed. This can be incredibly useful in pinpointing the specifics of your dog’s compensation, and can help guide the diagnostic process.

Consult a Specialist

A board-certified neurologist or sports medicine veterinarian can assess your dog during a manual exam, determine where exactly your dog is painful, and order advanced imaging like musculoskeletal ultrasound or MRI to properly assess the affected structures and make a definitive diagnosis. Some clinics also have pressure plates to objectively assess loadbearing in each limb. This technology can also be used to perform a pressure sensitive (objective) gait analysis.

Request a Pain Management Trial

A pain management trial usually runs 6-12 weeks, and includes a multi-modal pain management approach, leveraging the mechanism of action of a variety of pharmaceuticals to help control pain without negative side effects like heavy sedation, nausea, liver/kidney impacts, etc. Your GP vet *should* be able to assist you with this, but sometimes this is better managed by a neurologist, sports medicine vet, veterinary behaviorist, or veterinarian with a special interest in pain management (CVPP).

Short or Long-Term Lifestyle Modification

In the short-term avoiding high impact activity like dog-on-dog play, running up/down stairs, and jumping into / out of the car. Laying down carpet runners over slippery surfaces can prevent underlying issues from becoming worse. Limiting or eliminating spine extension, and end range hip extension can be helpful until further investigation can take place. These movement patterns are contraindicated for many/most of the musculoskeletal issues underlying compensatory pacing and gait changes.

But my dog’s breed has pacing in their breed standard!

This is actually a myth. Breeds like the Old English Sheep Dog, English Springer Spaniel, and Neapolitan Mastiff will demonstrate an ipsilateral gait when moving at lower speeds. This is expected in all dogs. BUT all healthy dogs, regardless of breed, should easily be able to transition out of a pace and into a trot given enough speed. No breed should be using a pace exclusively at trotting speeds, and there is no breed standard, that I have found, that suggests the breed should pace instead of trot.

Also, just because a particular breed standard fails to penalize pacing does not mean that the pacing is not caused by an underlying issue inherent in the breed that warrants further investigation. LTV, stenosis, and cauda equina syndrome are all diseases with an underlying genetic component.

What Should You NOT Do If Your Dog Paces?

- Do NOT approach pacing like a training issue, and try to train your dog to trot.

- Do NOT use cavaletti poles or other equipment to try to “force” the dog into a trotting gait.

- Do NOT seek chiropractic adjustments or spinal manipulations, as these are contraindicated for many of the underlying issues associated with a pace.

- Do NOT continue with sports, high impact activities, or rough dog-on-dog play. Temporarily pause these activities until appropriate imaging is done, and the cause for the pacing is uncovered.

Conclusion: Pacing in Dogs is Not More Efficient—It’s a Red Flag

Despite the myths in the dog world, pacing is not an energy-efficient gait for dogs at trotting speeds. Instead, it often signals an underlying biomechanical issue that requires attention, and further investigation. Understanding your dog’s movement can help ensure they stay healthy, comfortable, and capable of moving efficiently in the long term.

If your dog is a habitual pacer, consider scheduling a Gait Analysis Consult, and /or evaluation by a board certified veterinary neurologist or sports medicine vet to investigate the underlying cause.

0 Comments